Champlain’s Missed Rendezvous

It’s one of the most significant missed rendezvous in Canadian history – and one of the grandest journeys. Samuel de Champlain, explorer and champion of a fledgling French Canada, had been late for a gathering of native leaders near what was to become Montreal in the spring of 1615. He rushed to catch up with them using two canoes and 10 skilled, mostly indigenous, canoers. They paddled and portaged up the Ottawa River, across Lake Nippissing and down the French River to Georgian Bay – then down the length of its rocky eastern shore with its 30,000 granite islands and wind-blown, scraggy jack-pine trees. After 800 kilometers in 23 days, they arrived suddenly at what must have seemed like an Eden – good farmland and corn farmers in what’s now called Huronia in northern Simcoe County.

That transition in geography is just as unique today as it was then – as anyone who drives south on Ontario Highway 400 from Port Severn into Simcoe County – from a Precambrian landscape to quality farmland – can attest.

This would not have been Champlain’s first encounter with corn farming. Some indigenous farming was done on modest scale by nations along the Ottawa River through which he had travelled. He likely saw corn fields during his historically significant trip to Lake Champlain country in 1609 where he and his companions encountered and shot several Mohawk warriors. But the scale and grandeur of farming in Huronia would still have been a huge surprise.

(After reaching Huronia, Champlain became part of a large group of Huron and Algonkian nation warriors who attacked an Onondaga town near what’s now Syracuse, New York – a raid which was actually the reason for the missed appointment in Montreal and a fascinating story in itself – but I won’t enlarge here. You can read about it all in the classic, Champlain’s Dream, by D. H. Fischer)

Champlain spent that autumn and winter in Huronia visiting about 20 Huron and Petun towns/villages, who collectively called themselves, ‘Wendat.’ His detailed records of what he saw constitute much of what we know about this remarkable farming society during the mostly pre-European-contact era (“mostly” because some European goods were present in interior indigenous communities decades before the arrival of the first European explorers, thanks to well-developed indigenous trade networks).

Champlain estimated that the Huron confederacy numbered about 30,000 people, including towns as large as 5000 residents. When combined with an estimated 15,000 Petun people living just a few km to the west, this represents a Wendat population about as large as what exists in northern Simcoe County today.

These communities were all based on the growing of corn – huge quantities of corn in huge fields. Champlain reported seeing fields as large as 1000 acres and Gabriel Sagard, who wrote about Huronia 15 years later, said, “[The large fields were] the reason why going alone sometimes from one village to another I usually lost my way in these cornfields, more than in the prairies and forest.” The Wendat grew corn in quantities sufficient to produce food reserves for two or more years and also for trade with neighbouring non-farming Algonkian nations – trading for furs and materials such as copper from near Lake Superior. The Wendat did grow plants other than corn (primarily beans, squash, sunflower and tobacco) and their meals sometimes contained meat and fish, but their diet was dominated by corn.

I’ll come back to Huronia later, but first I want to shift back to an era 600 years or more earlier.

The Beginnings

Most readers will know about the transition of wild teosinte into corn (or maize) in Mexico about 5000 BC. From this beginning, corn culture moved slowly northward, entering the southwestern United States in about 2000 BC. It became the basic food for several native societies that flourished in New Mexico, Arizona and adjacent states up until about 1000 AD.

From the southwestern United States and/or northeastern Mexico, corn worked its way north and east, and especially along the Mississippi River system, where it flourished sometime after 800 AD. The largest example of a Mississippian, corn-based civilization is the former city of Cahokia in Illinois, near St. Louis. It peaked from about 1000 to 1400 AD and likely had a population in excess of 25,000 people. Cahokia was the largest city north of Mexico at the time – indeed, matching or exceeding some major European cities in size. This was a city and civilization based on corn, but supplemented with some other food crops.

There were many other smaller but significant corn-based communities elsewhere along the Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio river system. Corn culture spread up the Ohio River valley – then via the Alleghany River into the present New York State – and from there a few kilometers north into the present-day Ontario.

Estimates as to when corn entered Ontario vary. Some say as early as 500 AD. Georges Sioui, in his book Huron Wendat, The Heritage of the Circle, refers to a radiocarbon dating to 615 AD of corn residue found near Rice Lake Ontario. A summary by the Ontario Archaeological Society claims the presence of corn in Ontario near the end of what’s known as the Middle Woodland period, i.e., 700-900 AD. There seems to be broad agreement corn’s dominance as a food source was well established in Ontario by 1000 AD.

When I first posted this column, I raised questions about how corn could have appeared in Ontario as early as 500 or 615 AD if it did not have a significant presence in the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys until a few several centuries later. I was also puzzled about how corn could have been grown in a sporadic manner during the introductory period given this crop’s vulnerability to wild animals. Small fields of corn within forests would have been decimated – just as they would now – by birds, raccoons, squirrels, deer and other animal pests, as well as over-run by weeds. It would seem that corn would have required decent season-long husbandry throughout the full season in order to ensure anything much at harvest.

Since the initial posting, I’ve learned both puzzles may have been answered – first by the discovery of corn remnants in southern Ohio dating back to about 200 AD – and second that corn was far from the first farmed crop in Eastern North America. Bruce Smith and others have provided documentation that corn was actually a ‘Johnnie-come-lately’ to crop agriculture in this part of North America. Other plants including sunflower, cucurbits (gourds), and some chenopod species (lamb’s quarters and goosefoot) were domesticated and grown as farmed crops (i.e., planted, tended and harvested – and with plants being modified genetically by human selection) as early as 2000 BC – two millennia before corn. By the time corn arrived as an imported species from Mexico and the southwestern United States, farming skills would have been well developed (even if farmed crops did not yet dominate the human diet).

Given that corn was present as a minor species in Ohio in about 200 AD, it’s not unreasonable for it to have arrived in Ontario by 500 or 600 AD, as noted above.

A large puzzle remains: If corn was present in middle/eastern North America by 200 AD, why did it take until at least 800 AD – and perhaps after 900 AD – before it became a major food crop in the Mississippi/Ohio river basins?

That this is so has been determined by analysis of the relative presence of the carbon isotope C-13 in human bones. The ratio of C-13 to C-12 (the usual form of carbon) is higher in organic compounds created by C4 photosynthetic species like corn than with most other farmed and wild plant species that have C3 photosynthesis. A higher concentration of C-13 in human bones, caused by a corn-dominated diet, was not apparent until after 800 AD.

Smith suggests that corn may have been used primarily for ceremonial purposes before 800 AD (like tobacco), or perhaps a long duration was required until productive corn varieties adapted to longer summer day lengths had evolved. (Neither explanation is that convincing in my view.)

In any case, the transition to a corn-dominated food system, once it began, spread rapidly within a period of 200 years or less from the Cado culture in eastern Texas right through to southern Ontario.

Archaeological records show corn was well established in southern Ontario by 1000 AD and indigenous people were highly dependent on corn for food, centuries before their first contact with white man.

Ontario Corn Farming After 1000 AD

Thanks to the efforts of Ontario archeologists, we actually know a great deal about indigenous peoples in Ontario beginning 1000 AD. Most of southern Ontario and up-state New York was populated by people who have been collectively called ‘Iroquoian.’ The Ontario Iroquoian were closely related to other indigenous nations in states south of New York, but were surrounded on the west (Michigan and extreme southwestern Ontario), north (about everything north of Huronia) and east (Ottawa Valley, most or all of Quebec, Atlantic Canada and New England) by a much larger group of nations known collectively as Algonkian. The Algonkian people in Michigan and New England were also corn farmers, but in Ontario and Quebec they were dependent (with a few exceptions) on hunting and fishing – and on trade for corn with nations like the Wendat.

(A note on indigenous names is in order here: I am not aware of any reaction to ‘Algonkian,’ but ‘Iroquois’ and ‘Iroquoian’ seem to be universally disliked by those so labelled. ‘Haudenosaunee’ or ‘People of the Longhouse’ are what I’m advised by a Mohawk friend to use to refer to the collective Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora members of the Six Nations Confederacy. But when I asked him about the inclusion of the Wendat and other such nations, he had no advice. Wendat author Sioui recommends ‘Nandoueks’ to refer to the larger grouping, though I note he says it refers to “Wendats, Iroquois and other ethnically related Native groups,” which doesn’t solve my problem. I’ve not seen ‘Nandouek’ used elsewhere; hence, my ‘solution’ is to use ‘Iroquoian’ for the collective but not ‘Iroquois’ for any of its component groups.)

Much is made of the ‘Three Sisters’ – corn, beans and squash – in North American indigenous agriculture; however, archeologists report no indication of beans or squash throughout southern Ontario until at least 1400 AD, and only one archeological report of a single sunflower seed before then (dating to about 1350). Tobacco, used for ceremonial/religious purposes, arrived in Ontario about as early as corn.

Much of southern Ontario was unoccupied for extended periods of time and the occupied areas changed over the centuries. At the time of Champlain’s visits, in addition to the Huron and Petun, there were about 40,000 people known as Neutrals to the French – or Attawandarons to the Wendat – who lived roughly within the triangle between Oakville, St. Thomas and the Niagara River. Although information about the Attawandarons is much sparser than for the Wendat, it’s clear that their culture was almost identical.

There is ample evidence of Iroquoian culture north of Lake Ontario and into eastern Ontario during years prior to Champlain – people were closely related either to the Wendat, or to the Onondaga and Oneida people concentrated southeast and east of Lake Ontario.

When French explorer Jacques Cartier visited the sites of present-day Quebec City and Montreal in 1534-1535, he encountered corn-growing people who are now considered to have been members of the Onondaga nation. However, there was no sign of them when Champlain arrived about 70 years later; they are presumed to have been decimated by European diseases and/or warfare with Algonkian nations to the north.

Iroquoian Corn Culture

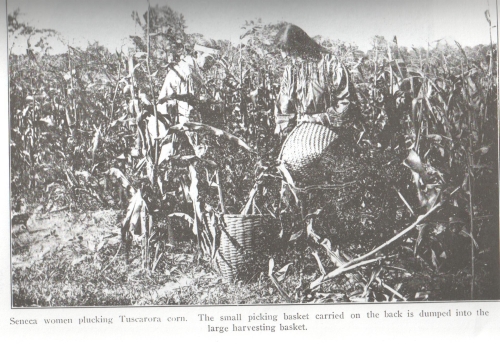

From F.W. Waugh. 1916. Iroquois Foods and Food Preparation

There is a good amount of available information on the culture and nutrition of Iroquoian nations, both from Europeans associated with the Huron people (Récollet and Jesuit missionaries as well as various visitors who wrote), and from similar writings about the Six Nations in New York State (especially the Seneca people who lived southeast of Buffalo). Details on how that corn was grown and on the many dozens of food dishes based thereon, are well described in two historically important books – by A.C. Parker, NY State Museum, 1910, and F.W. Waugh, National Museum of Canada, 1916. (Details are provided below.)

They grew flint, dent (they called this ‘she-corn’), sweet and pop corn with the occasional mutant ear of pod corn as well (developed glumes around each seed), and both white and coloured. Effort was taken to ensure varietal purity, though some cross pollination was encouraged. The well-tillered plants usually had two to three ears per stalk, and 100 to 400 kernels per ear.

The men cleared the land by girdling trees and burning the dead tree skeletons a year or two later. Except for that, corn farming was done by women with help from children and slaves. (There is not much information in what I’ve read about slaves other than to acknowledge their existence; I’ve guessing that their numbers were quite small.) Corn seeds were planted, several at a time, into holes three feet or more apart. The seed was often treated with a water solution containing extracts of several wild plants to discourage crows.

Dead weeds from the previous year were cut off and removed at planting time. Weeds were removed by hoeing throughout the season. Fields were sometimes burned after harvest or before planting in springtime for pest/weed control.

After corn emergence, beans were planted, sometimes in each hill, sometimes in every seventh hill. Squash was commonly planted between rows. Fertilizer was not used though ashes would have provided some nutrients and beans may have provided some legume nitrogen. Only certain East Coast tribes used fish as fertilizer and there is evidence that this technique was adopted only after contact with Europeans.

Worth noting is that these folks were totally into no tillage, the only tillage being the opening of holes for seed planting with a sharpened stick, a piece of deer antler or something similar. Even the most ardent no-till farmer in the 21st century does more tillage at seeding time than that.

Harvesting began with immature ‘green’ corn, some of which was roasted and preserved for winter food. Then came dough-stage harvesting, and finally mature corn. Several foods were made from corn at each stage. Mature corn was harvested, husks attached, and carried to the village or a central location where all but two or three husks were removed – generally at large social bees. (They say young men often helped because it was a good place to meet girls.) Remaining husks were breaded to form strings of ears which were then suspended from the roof, walls and interior posts of longhouses until dry. Most ears were then shelled and the grain placed in large bark bins up to six feet in diameter and height (up to 130 bushels) – generally within the longhouses, though sometimes outside with bark roofs.

Harvested ears were also stored in cribs made of poles and bark or, when dry, in long-term, hidden, underground granaries. These granaries, on well-drained sites, were commonly five-foot deep, lined with husks, grass or boughs, and covered when full with these same materials and then soil. In fact, the lucky discovery (and theft, some say) of in-ground corn granaries prevented the Pilgrims from certain starvation during their first winter at Plymouth in 1620-21.

Enough corn was grown to provide a two- or three-year supply and also for trading. Fur traders were regular customers in later years.

French governor Denonville and his troops spent ten days in 1687 burning Seneca corn bins and wrecking crops east of Niagara. His claim of 1,200,000 bushels destroyed seems high, but they did demolish lots of corn.

In 1779, General Sullivan, as directed by George Washington, destroyed 40 Seneca and Cayuga villages and an estimated 160,000 bushels of corn.

The Jesuits report the average Huron diet was 65% corn, for a daily corn consumption of 1.3 pounds – or 8.5 bushels per person per year. For a village of 2000 this meant about 17,000 bushels, or 430 tonnes. Two years’ supply, plus corn to trade, meant grain stocks of at least 35,000 bushels (20 to 30 semi-trailer loads) – all carried in baskets for up to six miles from fields to the village. No wonder that early visitors reported Iroquois villages full of corn.

I can find no accurate record of yields though 30 bushels/acre seems reasonable, based on several sources. Hence, a village of 2000 might require 600-1200 acres of corn. The Lawson Prehistoric Indian Village museum (London) says the original settlement there numbered 2000 with at least 600 acres of crops.

References listed below provide ample details on planting and harvesting, and the many ceremonies and religious events associated with both.

From A.C.Parker. 1010. Iroquois Uses of Maize and Other Food Plants

Decimation of Wendat and Attawandaron in 1649-1651

This culture flourished in Huronia and among the Attawandaron until 1649-1651 when the Wendat and Attawandaron communicates were attacked and annihilated by the Five Nation Confederacy from New York State (later to become Six Nations when the Tuscarora nation from North Carolina moved north in about 1720). Although these were all Iroquoian people, there had been long-term hatred between Ontario- and New York-based nations. The attack was instigated partly because of that and partly because of a need for more beaver pelts for trade to Europeans. (The Wendat blocked direct trade between the Five Nation Confederacy and Algonkian nations to the north.)

The Wendat and Attawandaron numbers were badly weakened at the time by deaths caused by European diseases. Also significant was a split within Wendat society caused by the conversion of some of them to Christianity by Jesuits. (Converts were encouraged to avoid contact with those who weren’t.) In any case, after about 1651, the Wendat and Attawandaron communities in southern Ontario were no more. A few of them went to a new Lorette reserve near Quebec City, some to the Walpole First Nations near Wallaceburg. Some ended up in the Wyandot Reserve in Oklahoma. Some were absorbed by the Five Nations themselves, either as citizens or slaves. Only their memory remains in Huronia and the Attawandaron lands to the south.

In the decades to follow, some Iroquoian settlements were established in southern Ontario, especially along the north shore of Lake Ontario; the present Toronto and Prince Edward County were two sites. These were subsequently driven out before 1700 by Algonkian nations from the north, especially the Ojibwa who were known in the Toronto-Hamilton-Guelph area as Mississauga.

The Ojibwa were not farmers, at least not initially, and their culture in southern Ontario was mostly one of hunting and fishing. However, a series of land transfer agreements after 1780 meant that the Ojibwa people ended up in a number of mostly small reserves with limited potential for hunting. Though the land on most of these reserves is not well suited to farming, concerted efforts by government-appointed ‘Indian agents’ to promote agriculture meant that many Ojibwa people became farmers to some extent.

Six Nations Come to Ontario

The final chapter of indigenous farm culture in Ontario involves the Six Nations. In 1779, US army troops directed by General Sullivan and sent by George Washington destroyed the corn fields of about 40 Six Nations towns/villages in western New York State. (Washington accused the Six Nations of aiding the British though history suggests they were, on balance, neutral.) The resulting starvation forced the people to move near Fort Niagara on the east side of the Niagara River near Lake Ontario, to secure food supplies from the British. That relocation included temporary settlement in what’s now Ontario, west of the Niagara River. After the US War of Independence, Six Nations peoples were granted land along Ontario’s Grand River, and they settled at and southeast of the site of present city of Brantford. Some also settled in the Tyendinaga reserve near Belleville and on reserves near Cornwall Ontario, Montreal, and along the Thames River between London and Chatham Ontario.

The story of these settlements has been well described in many other places (including Arthur Ray’s book, I Have Lived Here Since The World Began, An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native People) and will not be repeated here. The Six Nations brought their corn-based culture with them and became well-respected farmers in Ontario on arrival. For a number of reasons, farming and corn growing diminished in the Six Nations reserves over the decades, but there has been a renaissance underway since the year 2000 – also a fascinating story, but beyond the scope of this article.

The European settlers in Ontario largely ignored corn except as a forage (silage) crop in most of the province, preferring to grow the grain crops that they had known in Europe (the exception being a few counties in extreme southwestern Ontario where corn remained dominant).

Then, starting about 1960, there was a resurgence in interest in corn in Ontario and within a couple of decades, it became, once again, the dominant grain crop in the province. Hence, the second millennium ended in Ontario just as did the first – with corn the dominant grain crop – albeit with a few changes in technology over those ten centuries.

Western Canada

Finally a note about corn in western Canada: Corn culture spread up the Missouri River Valley just as it did up the Ohio in years around and after 1000 AD. Corn was grown by the Mandan nation in the Dakotas, with evidence of it being grown in prehistoric times both north of Winnipeg and in south-western Manitoba. Wikipedia cites a reference stating that corn was grown by indigenous people at the mouth of the Red River, north of Winnipeg in 1790, a decade before the start of the Red River Settlement, though after the first visits by European explorers and fur traders.

Key References:

Cornelius, C. 1999. Iroquois Corn in a Culture-Based Curriculum. State University of New York Press.

Fischer, D.H. 2009 Champlain’s Dream. Vintage Canada.

Flynn, C. and E.L. Syms. 1996. Manitoba History: Manitoba’s First Farmers. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/31/firstfarmers.shtml

Ontario Archeology Society. The Archaeology of Ontario: A Summary. https://www.ontarioarchaeology.org/summary-of-ont-arch

Parker, A.C. 1910. Iroquois Uses of Maize and Other Food Plants. New York State Museum. (Reproduced by Iroqrafts, Iroquois Publications, 1983 and 1994.)

Schmalz, P.S. 1991. The Ojibwa of Southern Ontario. University of Toronto Press.

Ray, A.J. 1996. I Have Lived Here Since the World Began, An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native People. Lester Publishing.

Sioui, G.E. 1999. Huron Wendat, The Heritage of the Circle. UBC Press. (English edition, original published in French, 1994, by Les Presses de l’Université Laval).

Waugh, F.W. 1916. Iroquois Foods and Food Preparation. National Museums of Canada. (Facsimile edition, 1973, and reproduced by Iroqrafts, Iroquois Publications, 1991).

White, R. 1985. Ontario 1610-1985. Dundurn Press.

Wright, J.V. 1966. The Ontario Iroquois Tradition. Bulletin 210. National Museums of Canada. (Facsimile edition in 1973.)

Some good places for information:

Iroqrafts, Oshweken, Ontario. http://www.iroqrafts.com/

Huronia Museum, Midland Ontario, https://huroniamuseum.com/

Crawford Lake Iroquoian Village, near Campbellville, Ontario. https://www.conservationhalton.ca/park-details?park=crawford-lake

Lawson Archaeological Site, London, Ontario. http://archaeologymuseum.ca/discover-archaeology/lawson-site/

Column revised August 30, 2020