(Last revised January 4, 2020)

Corn is the biggest agricultural success story of the Americas, from its beginning as a wild grass 7000 or more years ago in Mexico to become one of three dominant food and feed crops of the modern world. Its emergence as the grain crop with yields that surpass that of all others coincides with the creation of hybrid corn.

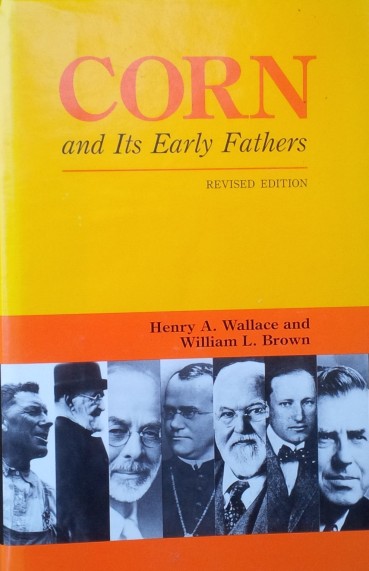

Several books have been written detailing the birth and early days of hybrid corn, including Corn and its Early Fathers, by Henry A. Wallace and William L. Brown, and Richard Crabb’s The Hybrid Corn Makers. Both are excellent. These and other references are listed at the end of this article. This article is written to provide a 5300-word (20 minute) overview for those lacking the time to read more.

The Beginnings of Hybrid Corn

Hybrid corn may represent the biggest agricultural miracle of the twentieth century. In fact, the full story begins back in 1694 when a Dutch botanist, Rudolph Camerarius discovered why corn pollen was needed for seed formation, and in 1716 in Massachusetts when Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister discovered the importance of wind pollination. Co-mingling of roots had previously been assumed responsible for genetic interactions between adjacent plants.

In the early 1800s, John Lorain, an innovative Pennsylvania farmer and writer, learned that natural cross pollination between southern gourdseed varieties and northern flints produced a new type of corn with intermediate kernel (i.e, “dent”) characteristics and higher yields.

Credit for the first professional interest in hybrid corn generally goes to Professor James Beal, a botanist at the Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University) who, in 1879, crossed two open-pollinated varieties for the sole purpose of increasing yield. Beal got the inspiration from Professor Asa Gray, one of his former professors at Harvard University. Gray, in turn, was a friend of Charles Darwin who had discovered the increased plant vigour that occurs when unrelated corn varieties are crossed. Beal’s initiative was not pursued commercially.

In 1896, Professor Cyril Hopkins at the University of Illinois began ‘ear-to-row’ selection for corn lines that were either high or low in either protein or oil, starting with the common variety, Burr White. In 1900, he hired a recent graduate, Edward M. East, to help with the project. In addition to managing Hopkins’ project, East and a couple of university colleagues began to inbreed corn, starting with another popular variety, Leaming. When East took a position at the Connecticut Experimental Station in 1905, he took the inbreds with him, and in 1907 began yield testing hybrid crosses involving the Leaming inbreds.

Simultaneously and independently, Dr. George Shull began work in 1905 just a few miles away at the Carnegie Institute in Cold Springs Harbor on New York Island. He produced inbreds and hybrid crosses starting with seed of a white dent corn variety that he got from a farm in Kansas. Shull recognized that this could be a means of increasing corn yields and gave talks stating such to American seedsmen in 1908, 1909 and 1910 – talks that were instrumental in triggering related research and commercial development in the US Midwest. However, Shull was a botanist more interested in genetics than agriculture, and he discontinued his research on corn because of bird problems in field plots, switching instead to Evening Primrose, Shepherd’s Purse and other wild species.

Both East and Shull recognized the potential value of hybrid vigour in increasing corn yields, but neither had a realistic plan for allowing farmers to benefit, given the very low seed yields of inbreds then available for use as single-cross hybrid seed parents. East envisioned a scheme based on crosses of open-pollinated varieties or ‘top-cross’ hybrids (pollen from inbreds used to pollinate silks of detasseled open-pollinated varieties) that farmers could do themselves. But no farmers were persuaded to do that. Shull considered his findings to be primarily of academic interest.

Dr. H.K. Hayes began corn inbreeding while he was an assistant to Dr. East at the Connecticut station and also a graduate student at Harvard University where East was a faculty member. Upon graduation, Hayes took a position at the University of Minnesota in 1915. He became a successful public corn breeder and a highly influential early promoter of hybrid corn – with a direct influence on the careers of several budding corn breeders.

Donald Jones, a graduate student and assistant to Dr. East hired after Hayes’ departure, invented double-cross hybrids. This involved a two-step process: four inbreds were crossed in pairs to produce two single-cross hybrids, and these, in turn, served as the seed parents for making double-cross hybrid seed that could be planted by farmers. Double-cross technology permitted hybrid seed to be produced in quantity at reasonable cost – a huge breakthrough allowing the large-scale use of hybrid corn in North American agriculture.

George S. Carter, a Connecticut farmer, used single-cross seed produced at the Connecticut station in 1920 to produce the first commercial-scale double-cross hybrid seed in 1921. He sold this to other farmers in 1922. His double-cross hybrid involved one parent produced using two Burr White inbreds, and the other from two Leaming inbreds. Thus, George Carter was the first person in the world to sell true hybrid seed corn.

Funk Brothers Seed Company, James Holbert and USDA

Eugene Funk and his family, based at Bloomington Illinois, were large farmers and seedsmen at the beginning of the 20th century. They were active in many aspects of Illinois agriculture and had developed their own open-pollinated varieties, Funk’s Yellow Dent and an earlier version, Funk’s 90-Day. Both were derived from the Midwest’s best-known variety at the turn of the century, Reid Yellow Dent. Reid Yellow Dent, in turn, was developed by Robert Reid and his son, James, in Illinois during the mid-to-late 1800s. It continues to be the most important original source for North American corn inbreds today, including various versions which were common at this time – one being an earlier-maturing version, Iodent, developed by Iowa State College, which figures prominently in the genetic background of many modern commercial inbreds.

(There is a large amount of older literature on the names and nature of the many open-pollinated (OP) corn varieties grown in about 1900. Discussion on them is beyond the scope of this article, but readers seeking more information are referred to an excellent, extensive review by Dr. A. Forrest Troyer, formerly with Pioneer, DeKalb and the University of Illinois. It is part of an equally impressive book called Specialist Corns edited by Dr. Arnel Hallauer of Iowa State University. Troyer’s review details the OP origins of many popular corn inbreds, including some from France. A non-pay-walled copy of the entire book can be down loaded from here.)

Funk began corn breeding including some inbreeding in about 1902. However, Funk reduced the hybrid work after a few years because of his inability to achieve yield improvements large enough to cover costs. Not discouraged, in 1915, Funk hired James Holbert, a new graduate from Purdue University, as his corn breeder. Holbert met Dr. Hayes at Minnesota, at time of graduation, and Hayes encourage him to concentrate on inbreeding and hybrid crosses – which he did. Holbert began inbred development almost immediately upon arrival at Bloomington, starting with the selection of 500 parent-stock ears chosen after the examination of more than one million individual plants.

In 1916, Funk Brothers Seed Company began selling seed of a product called ‘Funk’s Tribred Corn,’ the first so-called hybrid corn to be marketed anywhere – even if it was actually a cross among three unrelated open-pollinated varieties. The sale of this product stopped after a few years because the yield boost was insufficient to cover the added cost. Funk sold its first true double-cross commercial hybrid in 1927.

In 1918, following pressure on Washington by Eugene Funk to ‘do more’ about corn diseases, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) established a corn breeding research station on the Funk farm at Bloomington, with Holbert as its new corn breeder. This station operated until 1937 when it was closed (or transferred to the University of Illinois according to one reference) and Holbert returned to breeding corn for Funk Brothers. During his 19 years with USDA, Holbert provided free advice and breeding material to many fledgling private corn breeding programs, and developed several important early inbreds and public hybrids.

Some of the early Holbert/USDA inbreds were called ‘A,’ ‘B,’ ‘Hy’ and ‘R4,’ and double-cross hybrids were produced by combining these with early inbreds, Wf9 and 38-11, from Purdue (the Purdue corn breeder was Ralph St. John), and L317 from Iowa State College (ISC, later to be named Iowa State University, with Dr. Merle Jenkins as the breeder). US 13 was an early double-cross hybrid with the pedigree, (Wf9 x 38-11) x (Hy x L317).

Funk Brothers was perhaps the most important commercial seed corn company in the central Cornbelt in the marketing of open-pollinated corn varieties and in early hybrid development during the first third of the 20th century. Funk’s was a prominent name in hybrid corn for many decades to follow.

In my era, Funk hybrid names/numbers always began with the letter, G. I finally discovered the explanation in The Founding of Funk Seeds, produced by the company in about 1983 (not available on the web). Apparently, at the beginning, farm publications in the US Midwest were reluctant to publish company names in their articles, only hybrid numbers. So Funk included the letters B and G in some of their hybrid names, hoping farmers would associate the letter with the company. No one seems to have recorded why B and G. By chance, G hybrids turned out to be better than B, so B was soon dropped. And Funk’s hybrid numbers all began with G in years to follow.

Eugene Funk died in 1944 and Jim Holbert in 1957. In 1967, ownership of Funk Brothers Seed Company was acquired by CPC International, a New Jersey-based corn processor that had extensive starch milling operations in Illinois, and with which Funk had had a cooperative working relation in Italy since Wold War II. That sale was considered by some to have seriously impaired Funk’s long-term success. The new owner placed a major emphasis on developing hybrids that were high in oil content (matching CPC’s then lucrative market for Mazola corn oil, a by-product of starch milling). This meant reduced attention to agronomic traits like higher yield and standability (resistance to lodging) that were important to farmers.

A high point for Funk’s was the year 1970 when this company’s hybrids proved resistant to a widespread epidemic of Southern Corn Blight. The reason was that, unlike most other companies, Funk recognized that use of a source of male sterility then widely used in hybrid seed production caused susceptibility to the disease. Funk retained use of hand detasseling in seed production and its sales soared temporarily. The hybrid Funk’s G4444 soon became the most popular hybrid in the US Midwest in the early 1970s – replacing DeKalb XL45 that had been the favourite in the decade before. Funk’s G4444 was actually a cross between two public Minnesota inbred (A619 and A632), which means that it was likely also available from other companies, but it was sure a commercial success for Funk.

But poor stalk quality was to damage the marketing fortunes of Funk’s trademark ‘G’ hybrids by the mid 1970s and farmers switched to competitive products, especially new hybrids such as P3780 from Pioneer with superior standability. Sales of Funk corn hybrids plummeted. Funk hired two well-respected university corn geneticists, in turn, to lead its corn research program – Dr. R.I (Bob) Braun from McGill University in Quebec and Dr. Steve Eberhart from Iowa State University (both of whom I knew and admired.) But it made no difference; Funk seed sales plunged.

Funk became a public company in 1972 with the name changed to Funk Seeds International. It was purchased by the Swiss chemical/ag-chemical company Ciba-Geigy in 1974. The name trade name, Funk’s, was discontinued by Ciba-Geigy in 1993 – a sad ending for such an important name in US and Canadian corn history.

Ciba-Geigy merged with another chemical company, Sandoz to form Novartis in 1997 and a further merger with AstraZeneca led to the creation of Syngenta in 2000. Syngenta is now owned by ChemChina and Syngenta sells seed corn under the NK trade name. (‘NK’ comes from Northrup-King, a Minnesota-based seed company dating back to the 1800s that was purchased by Sandoz in 1969.)

Note that there was an unrelated and smaller corn seed company based in Indiana called Edward J Funk and Sons that used the tradename ‘Supercrost.’ The two Funk companies were often confused. The Edward Funk company was sold in 1990 to the Garst Seed Company, Garst then being owned by a British chemical company, ICI. ICI later merged its various seed operations to form Zeneca. And through a subsequent merger with a Swedish firm, Zeneca became part of AstraZeneca.

In addition, Funk Brothers Seed Company had a number of ‘Associated Growers’ that were licenced to produce and market Funk G hybrids as independent companies. Funk seed corn production and sales in Canada were managed by an associate company in the 1940s. After the sale to Ciba-Geigy in 1974, several of these associates formed their own company that they named Golden Harvest. It was later purchased by Syngenta, though seed corn is still sold as ‘Golden Harvest’ hybrids in the United States.

Henry Wallace and Pioneer Hi-Bred Corn Company

The Wallace family name is legendary in Iowa starting with the first Henry Wallace who arrived in the state as a Presbyterian minister in 1862, then became farmer, and later editor-in-chief of a publication called the Iowa Homestead. His son Henry C. Wallace purchased another farm paper, which he renamed, Wallace’s Farmer, and served as a professor of dairying at Iowa State College (ISC, later Iowa State University). In 1921, he became the US Secretary of Agriculture.

Henry C’s son, Henry Agard Wallace, was born in 1888 and became an entrepreneur interested in corn improvement at an early age. As a youngster, he sold his first seed corn, 10 bushels produced from a cross between two open-pollinated varieties for $50. At age 16, he challenged the then-popular assumption that seed from ears of championship ‘show corn’ would produce superior crops the following year. A special yield test run by ISC and instigated by teenager Henry A and his dad, Henry C, showed that Henry A’s skepticism was well founded. Plants grown from show-ear seeds yielded no more.

The fallacy of superiority of show corn – which had only became a popular feature of fall fairs in the Midwest during the 1890s – impeded corn advancement for at least three decades to follow. Support for the assumed supremacy of show corn was so strong that it affected the judgement of corn industry leaders everywhere. Varietal yield trials, up until then largely unknown, began in Iowa in about 1920, spreading soon to other states and Ontario, and were effective in finally destroying the myth. If anything, plots grown from seed of show-corn-winning ears often yielded below average. Nevertheless, the modern view of what a ‘good-looking’ ear of corn should look like still stems from the corn-show era.

Henry A graduated from Iowa State College in 1910 and started corn breeding in a 10-foot-by-20-foot garden behind the family home in Des Moines in 1913. This was soon followed by more extensive breeding – though still tiny by modern standards – on a nearby farm owned by his uncle. A single-cross hybrid called Copper Cross developed by Wallace – which was a cross between an inbred from the variety Leaming and another from Bloody Butcher (known for its dark red kernels) – was entered in a newly created regional varietal performance trial. The hybrid yielded first in 1924 and its seed was produced on one acre of land near Altoona Iowa under contract with George Kurtzwell of the Iowa Seed Company. (Kurtzwell’s sister later proclaimed she detasseled Iowa’s entire hybrid seed corn crop that year.) The resulting 15 bushels of seed was sold in 1925 for $1 per pound.

Copper Cross was not a commercial success because of the low seed yield. Indeed, it was only sold for one year, and Wallace and partners shifted quickly to double-cross hybrids. But, as the first true hybrid corn sold in the US Midwest, the historical fame of Copper Cross is assured.

The corn program moved to newly purchased land at Johnston, north of Des Moines, at about this time. The Hi-Bred Corn Company was created by Wallace and two partners in 1926. It was renamed Pioneer Hi-Bred Corn Company in 1935.

As well as being a visionary and entrepreneur, Henry A. Wallace was a great communicator and promoter, and his ceaseless promotion of hybrid corn in Wallace’s Farmer was critically important to the fledgling hybrid industry.

The ‘farmer-salesman’ approach adopted by Pioneer in the 1930s worked remarkably well and is still the basis for most corn seed sales by major companies across North America.

Henry A became U.S. Secretary of Agriculture in 1933 thus ending his direct involvement with Pioneer. He later served from 1941 to 1945 as vice-president of the United States under President Roosevelt. Among other accomplishments as secretary and vice president, Henry A played a critical role in the creation of the Rockefeller-funded corn and wheat improvement program (later, CIMMYT) in Mexico.

Wallace attracted some outstanding people to his team including a farm boy and recent ISC graduate, Raymond Baker, who joined Pioneer in 1928. Baker became head of corn research in 1933.

I had the rare privilege of meeting Baker as well as author Bill Brown, then vice president of research and later to become Pioneer president, when I interviewed for a research position at Johnston in 1969. (The interview occurred in a nondescript three-story red-brick building on the Johnston property that was then the headquarters for the Pioneer corn research program – a far cry from the expansive Pioneer research campus that exists there today.) My interviewers also included Don Duvick and Forrest Troyer, two outstanding corn breeders and industry leaders, and good contacts in the years to follow. Such a rare opportunity for me (even though I did not take the offered job).

No story of the beginnings of Pioneer Hi-Bred is complete without mention of Garst and Thomas. An entrepreneur extraordinaire, Roswell Garst, persuaded Wallace in 1930 to let him produce Pioneer seed at Coon Rapids Iowa, about 50 miles northwest of Des Moines, and sell it in western Iowa and states further west. (Thomas was a minor player in the venture and his share was soon purchased by Garst.) This turned out to be a financial gold mine for Garst. It continued until his death in 1977 when Pioneer reclaimed these production/marketing rights. Garst’s son, Steve, established Garst Seeds in 1980; it was sold to Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in 1985. The rationale I’ve heard for the original arrangement with Rosell Garst (true or false??) is that Wallace did not expect his hybrids to sell as far away as Coon Rapids; therefore, the Garst and Thomas venture was not expected to compete with a Des Moines/Johnston-based business.

Pioneer Canada had a similar beginning with the initial business being that of a farmer and businessman who later sold out to the Johnston-based company. I’ll write more about the Canadian connection in a later column.

I also had the privilege of visiting Roswell (aka Bob) Garst and his various businesses in Coon Rapids in about 1972. Garst was a very colourful, aggressive and highly opinionated character who had became nationally famous for hosting Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev during his 1959 visit to Iowa. Bob Garst would have made Donald Trump look like a wallflower.

Pioneer’s seed corn business was sizable right from its beginnings but sales really boomed during the 1970s and years to follow, thanks to an earned reputation for stress tolerance and superior stalk quality. There is an intriguing internet thread here where Midwest farmers describe why they switched to Pioneer hybrids, and away from Funk’s, at that time.

Pioneer’s success might be credited to at least three factors: 1) extensive use in breeding of the Iowa Stiff Stalk Synthetic, a special population produced by Dr. George Sprague, a USDA breeder at Iowa State College based on early inbreds with superior stalk quality (reference here), 2) a huge pre-release hybrid testing program with many locations all across corn-growing regions of North America, and 3) a unique three-replicate testing process introduced by Don Duvick, then head of corn research. The latter involved one rep planted at a ‘standard’ plant density, one with 5000 fewer plants per acre, and one with 5000 more. I recall Don discussing this this over lunch in Chicago in about 1970. (I tried to persuade him to go with two reps at standard and two at 5000-plus – advise which he rejected.) He obviously made a brilliant decision that paid off hugely for the company. Pioneer became the North American leader in corn seed sales in 1981, and I think it has been there most of the time since. (It reached 67% of Canadian seed corn sales during the late 1990s though the percentage declined after then.)

The company changed its name to Pioneer Hi-Bred International in 1970 and went public in 1973. This coincided with a major company reorganization and expansion beyond North America including a new corn-breeding program in France. Pioneer was first traded publicly on the New York Stock Exchange in 1995. Twenty percent ownership was purchased by DuPont in 1997 and the remaining 80% in 1999. Following DuPont’s merger with Dow to form DowDuPont in 2017, Pioneer is now a brand name for the new corporate entity, Corteva AgriScience.

DeKalb Agricultural Association

DeKalb, the seed corn company, had its beginnings in 1912 as the DeKalb County Agricultural Association created by a northern Illinois farm organization, the DeKalb County Farm Bureau. The association had the goal of ensuring good seed quality for its members – an apparent problem at the time. Tom Roberts was hired as county agent and as the manager of the association. The association also hired Charlie Gunn who figured prominently in the corn-breeding program to follow.

In 1923, Roberts and Gunn invited Henry C. Wallace, then US Secretary of Agriculture, to speak at an association event (the train from Washington DC to Des Moines travelled through DeKalb) and Wallace shared his enthusiasm for corn improvement using hybrids. Roberts and Gunn began corn inbreeding in secret that summer but did not tell the association directors until five years later. This was done, apparently, to keep a local competitor in the seed business from knowing what they were doing.

New inbreds developed by DeKalb were crossed with later-maturing inbreds provided by Holbert at the USDA station at Bloomington IL to produce double cross hybrids. The first production of commercial seed was in 1934; a major drought that year meant only 325 bushel of hybrid seed was produced on 75 acres. The sale of this small quantity in 1935 represented DeKalb’s first sale of hybrid corn seed. Not discouraged, they produced 14,500 bushels on 310 acres in 1935 and 90,000 bushels in 1936. The genius of Roberts and Gunn was in producing large quantities of hybrid seed right from the beginning and advertizing aggressively, especially in the farm magazine, Prairie Farmer.

These advertizements resulted in requests for purchases from farmers all across the US Midwest, including maturity zones much different from northern Illinois. Ralph St. John, a prominent corn breeder Purdue University, was hired to serve as a corn breeder for DeKalb, focusing on longer-season maturity zones. Seed production facilities were established in Nebraska, Iowa and Indiana in 1938. The first DeKalb corn was sold in Ontario in 1939.

Four million acres of the Midwest were planted with DeKalb hybrids in 1940. The hybrid, DeKalb 404A, introduced in 1940 became hugely popular in the central Cornbelt, with more than 500,000 bushels of seed sold in 1947. That was followed by XL45, an earlier maturing hybrid that proved highly successful during the 1960s – with its fame enhanced when Clyde Hight used it to become the first Midwest farmer to average more than 200 bushels of corn per acre on a substantial acreage.

DeKalb was the largest US seed corn marketer from the mid 1930s until the 1970s when it was surpassed by Pioneer.

The DeKalb Agricultural Association was renamed DeKalb AgResearch in 1968. A joint venture with Pfizer in 1982 resulted in the name DeKalb-Pfizer Genetics that became the DeKalb Corporation in 1985. The seed portion was spun off and named DeKalb Genetics Corporation in 1988. (The DeKalb Corporation also had extensive investments in non-agricultural ventures including petroleum.)

Monsanto purchased 40% of DeKalb in 1996 and the rest in 1998. With Monsanto’s purchase by Bayer completed in 2018, DeKalb is now a tradename for Bayer.

On a personal note, I was very close to DeKalb for several years during the 1970s when we combined to test some of my ideas for corn inbred selection (I was a crop physiologist with the University of Guelph at the time) in their commercial breeding system in northern Illinois. I was never a paid consultant though DeKalb did sponsor a couple of my graduate students. This ended when there was a major change in DeKalb research management – triggered by a major loss in market share to Pioneer – and I left the University of Guelph to work for a farm organization – both occurring in the early 1980s.

Lester Pfister and PAG

Lester Pfister, born in 1897, quit school at age 14 to farm near El Paso, Illinois, and thereafter developed a system for yield-test comparisons of open-pollinated varieties. In that era, yield-test comparisons were very uncommon; farmers generally chose seed for the following year based on ear characteristics – usually as they hand-harvested the ears of their own crops – but also in purchases of seed ears from neighbours. (Farmers would commonly pay more for seed still on the ears – versus shelled – so they could see what the ears looked like.) From this beginning, Pfister developed a variety called Krug Yellow Dent that became very popular in central Illinois. He began inbreeding Krug in 1925.

Pfister struggled with near financial ruin caused by the Depression and droughts in 1934 and 1936 but persevered, producing 37,000 bushels of hybrid seed for sale in 1937, generally using inbreds provided by Holbert at the USDA station at nearby Bloomington. Pfister also benefitted from some national publicity generated by a feature story in Life magazine that claimed he was the inventor of hybrid corn. He used this publicity very skillfully to expand his business.

Pfister’s approach to production and marketing was almost the opposite of DeKalb’s. Pfister recognized that he could not produce and market seed on a competitive scale for the entire Cornbelt, so he developed a system of associated growers – similar to Funk’s – that was well-developed by 1943. In fact, that year the franchised growers purchased the parent company from the Pfister family to become a cooperative called Pfister Associated Growers. It became the P.A.G. Division of W.R. Grace, a fertilizer/chemical company, in 1967.

P.A.G. Seeds became a division of Cargill in 1971 or 1972 and the brand name changed to Cargill Seeds in 1987. It was then bought by Dow Agrosciences in 1998 and merged with Dow’s existing brand, Mycogen, to form Dow Seeds. It is now part of Corteva Agriscience following the 2017 Dow-DuPont merger.

As an aside, when I started farming near Guelph in 1972, two of my earliest hybrids were PAG SX42 and SX47.

Public Corn Breeding

In this article, I have focused on commercial hybrid corn pioneers rather than public breeders. That’s partly for brevity (recognizing that the article is not that brief, in any case) and partly because their histories are more interesting and less well known.

However, it’s important to give credit to the role of public breeders. USDA, which converted its corn research effort to a dominant emphasis on corn hybrid development in about 1921, was responsible for many early inbreds and hybrids. US 13 was one of the earliest hybrids, created by Holbert at USDA-Bloomington, but there were many others.

Work at the University of Illinois, the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, the Carnegie Cold Harbor laboratory on Long Island, New York has been described, along with public corn breeding at the University of Minnesota, Iowa State College and Purdue University. But other land-grant programs in the US Midwest also established inbred and hybrid development programs at an early date including Ohio, Nebraska, Missouri and Illinois.

The hybrid Iowa 939, which was also sold under other names, was an early success. It was even grown in Ontario in the late 1930s even though too late in maturity to be considered adapted.

I’ll make special mention of the corn breeding program of Dr. Norman Neal at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Neal was a New Zealander who came initially to Wisconsin to study perennial forages. However, a temporary job in the breeding nursery of Dr. Alexander Brink (Brink is better known for his pioneer work on alfalfa breeding but also worked on corn) to earn some needed cash, led to a life-long commitment to corn. Closely associated with Neal‘s program, from which hybrids were made available to farmers as early as 1933, was an associated corn breeding program of A.M. Strommen at the Spooner research station of the University of Wisconsin, many miles further north. Some great early-maturing inbreds from Madison and Spooner, Wisconsin formed the base for most early hybrids in the United States and Canada. In fact, a check of the list of hybrids approved for sale to Ontario farmers in the early 1940s showed that almost all were of Wisconsin origin, including the first known fields of hybrid corn grown in 1937. More on that will follow in a future column.

Early Expansion of Hybrid Corn and the Significance of Drought

The acreage of hybrid corn increased steadily after 1930, led by the State of Iowa, thanks in large part to the promotional efforts of Henry A. Wallace, Wallace Farmer and Iowa State College. However, it was probably the drought years of 1934 and 1936 that caused the greatest impetus. The drought of 1934 was severe and widespread across the entire Midwest, and the superior stress tolerance of hybrid corn was very apparent that year. Although the 1936 drought was centred further west (a total disaster in states like Kansas but not so bad in Illinois and eastward), it reinforced the lesson of 1934. Hybrid corn was more drought tolerant.

Richard Sutch (2010) has presented convincing evidence that drought was responsible more than anything else – including the typical yield boost from heterosis – for the major conversion of US Midwest corn acreage to hybrids by 1940.

Here are two graphs from Sutch’s paper:

The rapid expansion in hybrid corn acceptance led to a massive increase in the number of companies producing and marketing hybrid corn. A review by USDA of mergers and acquisitions in the US hybrid corn industry, completed in 2004, states that 190 companies produced and/or sold hybrid seed corn during the 1930s.

A Big Thank You

In the 1930s, the average yield of corn in the US Midwest was about 30-40 bushels per acre – as it had been for many decades before. Indeed, there are suggestions that this yield was trending lower in some areas of the United States, especially in the eastern Cornbelt, because of the combination of corn diseases and soil degradation; 100 years of farming by then had meant important reductions in soil organic matter content. The increasing prevalence of corn diseases was the reason for the establishment of the USDA corn research station on the Funk farm at Bloomington in 1917.

Some have argued that the yield benefit from hybrid technology has been overstated; perhaps if the equivalent amount of breeding effort had gone into the improvement of open-pollinated varieties, the superior yield levels of today (typical state averages of 170 to more than 200 bushels per acre) would still have been realized. But that said, it’s highly unlikely that this would have occurred without the profit incentive for corn breeding with hybrid technology and the need for farmers to repurchase seed each year.

Note that in the early days of hybrid corn, almost all inbreds were all publicly available and farmers had the right to produce their own hybrid corn seed if they chose to do so. In fact, very few did so and, of those who did, many went on to develop their own hybrid seed corn companies.

For many years, the number of small seed corn companies in the US and Canada was huge. Most of these would have sold hybrids produced from publicly available inbreds, meaning the same hybrids were available from many different suppliers. That’s not really true now for reasons of economies of scale which have reduced company numbers in almost every area of modern commerce, and the fact that almost all corn breeding is done nowadays by private companies.

Hybrid corn is a remarkable North American, and global, success story.

Acknowledgements and Reference Material

In addition to the links provided below, I thank the following individuals for their help in providing key references and links thereto:

Karen Daynard, Dr. Greg Edmeades, Dr. Gustavo Garcia, Dr. Peter Hannam, Daniel Hoy, Dr. Bruce Hunter, David Morris, Dr. Raymond Shillito, and Dr. Stephen Smith.

If you spot anything in this article which is factually incorrect, please contact me at TerryDaynard@gmail.com, so that the correction can be made. Thanks.

- General references on hybrid corn history

Crabb, Richard, 1992, The Hybrid Corn-Makers, Golden anniversary edition. West Chicago Publishing Company. (This edition includes a complete copy of the first edition, also by R. Crabb, published in 1948 by the Rutgers University Press.)

Hallauer, Arnel R. 2009. Corn Breeding. Iowa State University Research Farm Progress Report.

Sprague, George F., ed. 1977. Corn and Corn Improvement. American Society of Agronomy.

Sutch, Richard. 2010. The Impact of the 1936 Corn-Belt drought on American farmers’ adoption of hybrid corn. University of California, Riverside and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Troyer, A. Forrest. 2000. Temperate Corn: Background, behavior, and breeding. Chapter in Speciality Corns, second edition, ed. Arnel R. Hallauer. CRC Press. (Book can be downloaded here.)

United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2004. Mergers and acquisitions rose in the past three decades. Chapter from The Seed Industry in US Agriculture.

Wallace, Henry A., and William L. Brown. 1988. Corn and Its Early Fathers, revised edition. Iowa State University Press

- Funk Brothers Seed Company

Funk Bros. Seed Co. Publication date not stated but probably 1941. Funk Farms birthplace of commercial hybrid corn. A history of hybrid corn. Document 633.15709773 F963f. Illinois Historical Society.

Funk Seeds International. Publication date not stated but probably 1983. The Founding of Funk Seeds. Compiled by Dr. Leon Steele. Ciba-Geigy Corporation.

- Pioneer Hi-Bred Corn Company

Brown, William L. 1983. H.A. Wallace and the development of hybrid corn. The Annals of Iowa, State Historical Society of Iowa, Vol 47 (2), 167-179.

Dupont Pioneer milestones. Pioneer.com web site.

Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc. History. 2001. International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 41. St. James Press.

Jarnigan, Robert A. 2016. A brief summary of Pioneer history on the 90th anniversary. Reproduced from the Iowan magazine.

- DeKalb Agricultural Association

DeKalb Genetics Corporation History. 1997. International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 41. St. James Press.

Northern Illinois Regional History Center. Undated. DeKalb AgResearch, DeKalb, Illinois. Collection item RC 190.

Wikipedia. DeKalb Genetics Corporation. Web site.

- Pfister Hybrid Corn Company.

Broehl, Wayne G. 1998. Excerpt from Cargill, Growing Global. University Press of New England.

Fussell, Betty H. 1992. Excerpt from The Story of Corn. University of New Mexico Press.