A little over 45 years ago, equipped with not much more than strong curiosity, a list of contacts and my inadequate high-school French, I spent 3 weeks visiting corn researchers, farmers, and the Association Générale des Producteurs de Maїs (AGPM) in France. At that stage in my career I had spent 10 years in corn research and agronomy in Canada and the United States. But I had come to realize that the Canadian growing season for corn is actually more similar to France than most of the United States. It was time to learn more from our cross-Atlantic colleagues.

That trip was highly rewarding and four years later, I spent additional weeks there.

Not only did I experience an agriculture and corn culture notably different from that in Ontario, I was also seeing a French corn industry – as I realized years later – in the midst of major change.

I also met Jean-Pierre Gay, a corn geneticist/breeder and agricultural historian, who later gave me a copy of his new book entitled Fabuleux Maїs, histoire et avenir d’une plante, published by AGPM in 1984. It’s a history of corn from its very beginnings in Mexico to the early 1980s in France.

I was busy at the time, and still had only a rustic ability in French, so the book was skim-read briefly and put on a shelf. Now, almost 40 years later, I’ve had time to read Gay’s book completely – parts of it several times – and what I’ve discovered is one of the best chronicles of corn history I’ve ever read.

Fabuleux Maїs is full of details on the beginnings of corn in Meso-America, and its rapid establishment throughout many parts of Europe and Africa after Columbus’s journey in 1492. The history of corn in France is especially intriguing.

The book is available from Amazon, but only in French and only in non-electronic form (no option for Google Translate). So, for the benefit of those with no French language skill or who lack the time to read the full 296 pages, I’m providing the following brief summary. I’ve also added a small amount on corn advancement in France after the book was published (or at least the part with which I am personally familiar).

Corn Comes to Europe

Metallic gold was what the early Spanish explorers sought during their visit to the New World in 1492 and the years immediately thereafter. But the real gold they discovered is what we in English-speaking Canada and the United States call ‘corn’ – and ‘maize’ in other Anglophone countries, ‘maїs’ and ‘maiz’ in French and Spanish, Zea mays by scientists, and by dozens of other names around the world. Apparently, the original name in Europe might have been ‘mahiz,’ a name used by Cuban indigenous people who were likely the first corn growers that Columbus encountered.

(I am using the term ‘corn’ in this article for the simple fact that that’s the name with which I’m most familiar, and probably the term used by most of my readers, as well.)

Columbus brought corn back to Spain, and there is good evidence that white Caribbean flint corn was grown near Seville in southern Spain in 1494 AD.

Though Seville is far south in Europe, it’s still well north of Cuba, and given corn’s high photoperiodic sensitivity, it would have been very late in maturity (and quite tall). But that it was a success is shown by the rapidity with which its culture expanded through much of Mediterranean basin, and into Balkan countries to the north and east a few decades later.

Though the details are beyond the scope of this article, corn was also spreading rapidly elsewhere at the time. There is record of it in Indonesia in 1496, with early arrivals in India, The Philippines, South-east Asia and China). Portuguese traders and slavers were responsible for the first spread into Africa about 1550.

Gay says in Fabuleux Maїs that the original Caribbean flint corn was infused relatively quickly with imported corn varieties from Mexico including shorter-season varieties from the highlands, but no details are provided.

Interestingly, one of the first European visitors to what’s now known as Canada and the United States was a Frenchman, Jacques Cartier, who in 1535 travelled as far west present-day Montreal and reported encounters with corn-growing people along the St. Lawrence River including well east of the present Quebec City. However, there is no record of Cartier bringing back corn seed to grow in Europe. Of note, those St. Lawrence River farmers were all gone when Samuel de Champlain and other French explorers arrived again after 1600. (They are believed to have been members of the Mohawk and/or Onondaga nations who by 1600 were located near Lake Champlain and lands to the south and west.)

The spread of corn through the Old World was remarkably rapid though with few or no formal records kept of details, so that there was later confusion as to its origin. Corn was often referred to, in various languages, as ‘Turkish wheat’ with that country assumed to have been its original home. Some authors claimed there are references to corn growing going back to the ancient Egyptians and also in the writings of Homer (Greece) and Pliny The Elder (Roman). The assumption of an Old World origin was not that uncommon for a century or more to follow Columbus’ travels.

Corn Arrives in France

Map of France

With France, the story is a little different. The first record of corn there dates to 1523 in the Basque country, near the towns of Bayonne and Biarritz and in nearby French Béarn (extreme southwest, near the Atlantic, a few km from Spain). But the spread beyond there was slow and largely through the rugged poorer farmlands to the east and north-east of Toulouse.

There is also a lot of confusion about the early progress of corn growing in France as it was commonly referred to as millet, and confused with the grain of African origin with the same name – and sometimes with sorghum too. Thus, unless accompanied by a drawing or some reference to grain size, there is no way of being sure which species is being referred to in sporadic records from the south of France for a period of 100-150 years or more.

Corn did enjoy early popularity in extreme southwestern France. There is a record of 1000 tonnes being exported from this area to Spain in 1774. It formed about 70% of the local human diet – commonly accompanied by pellagra, a deficiency disease caused by the low content of the amino acids lysine and tryptophan in grain corn. (Indigenous American nations were subject to the same disease though generally countered it with co-consumption of beans, meat and fish.)

But beyond very southwestern departments, corn was very slow to become a common crop in most of France.

Corn did spread as far as Alsace in 1637 where it was called, interestingly enough, “Welsch korn.” There is some evidence (though not in Gay’s book) that this was the result of a second early entry of corn into southeastern France from northwestern Italy.

But French corn production remained tiny. The reasons for the slow spread were several:

One was that corn was not considered healthy to eat – perhaps linked to the pellagra problem, but also the generally impoverished and unhealthy condition of most people who lived in what was then regarded as a very backwards part of France. Unless humans were forced to eat corn, it was generally reserved for livestock feeding, with humans opting for foods produced from wheat (mainly) but also other small-grain cereals.

The more productive lands for grain production in France are generally in the west, north-central and north, where wheat and similar cereals reigned supreme.

By far the biggest obstacle seems to have been the church and a practice called ‘la dîme.’ (I don’t know the equivalent English name, if there is one.) La dîme was an historic practice by which farmers (mostly tenant farmers) paid a set amount per unit of land area to the church for the right to grow various crops. There were fixed per-ha rates for wheat, rye, barley, all the common food crops, but none for the ‘new’ crop corn. In return, the church discouraged the production of corn in various ways. The discouragement included spreading misinformation about its unhealthiness and association with poverty. Because much of the land was owned by large landowners who wanted to be assured of ultimate salvation, many of them inhibited corn growing on rented lands.

There were efforts made to pay the church amounts in lieu of the dîme. And though this might seem like an obvious solution, efforts to introduce a dîme for corn did not prove popular (one reason being that some farmers and landlords saw corn as a legal – though frowned-upon – way of avoiding the payment to the church). The dîme was one reason why those in agriculture many have deliberately confused corn with millet and sorghum – though I am not sure of the historic status of true millet or sorghum as dîme-requiring crops.

The result was that peasant farmers were allowed, generally, to grow a small amount of corn without hassle, but when it came to represent a substantial portion of cropped land, a visit from a church official was inevitable.

I have not seen information as to which ‘church.’ Though French Protestant Hugenots were still common in southern France for part of that era, I assume the dîme was a Roman Catholic practice.

My understanding is that the practice of dîme payments pretty much disappeared during the French Revolution in 1789, but the die was cast: grain corn was not considered a proper crop to grow in much of France – much less to eat – for up to four centuries after its first arrival in 1523. That continued well into the twentieth century.

Hence, land surface area devoted to corn did not grow consistently. According to author Gay, in 1840, 532,00 ha of corn were grown in France. But by 1943, that had declined to 217,000 ha, with half of that grown in two (out of a total of 96) French departments in the extreme southwest.

Beginning of the Modern Era for Corn in France

An important event occurred in 1930 in Pau, France – the Congrès International du Maїs, organized by a railroad company, la Compagnie des Chemins de Fer du Midi. (Why a railroad company sponsor? Author Gay says he does not really know.)

The Congress that emphasized the revolution on corn breeding then underway in the United States was a major success. Two years later, a corn genetics/breeding research station was established at Saint-Martin-de-Hinx (near Bayonne), and two years after that, in 1934, the Association Générale des Producteurs de Maїs (AGPM) was founded, based at Pau.

Although breeding efforts at Saint-Martin-de-Hinx continued through World War II, most other Congress-related activities including further development of AGPM stopped. AGPM was revived again in 1947 and a second international AGPM-led congress was held at Pau in 1949. This time the emphasis was mostly on hybrid corn and its success in the United States.

As a result, the production of hybrid corn and number of planted ha of grain corn grew rapidly, reaching 300,000 ha in 1948-50, with an average yield of 1.8 t/ha, to 600,000 10 years later and an average yield of 2.8 t/ha. (For those who think in bushels and acres, that’s about 45 bu/acre.)

The hybrids grown initially were exclusively of US origin, which led to two issues: 1) they were very late in maturity and adapted only to extreme southwestern departments, and 2) they were American.

There were many debates about whether corn grown from US hybrids was safe for the soil or to eat. There were complaints that US was actually foreign territory for corn and that emphasis should be on corn varieties from what locals considered to be its locally assumed ‘centre of origin’ – the Basque country and nearby Spain. There were also debates on whether the higher productivity with hybrids was a good thing. Hybrids took more skill to grow (less vigorous at the beginning than local open-pollinated varieties and required more fertilizer), and produced more corn than some farmers needed. (“After all, farmers have been able to grow enough feed for their animals using the older varieties,” some said. “Why change?”)

Nevertheless, corn continued to expand – at least in warmest parts of the country. The hybrids were too late in maturity to be grown on the better France farmlands generally in the north, north-central and western parts of the country.

The first use of the herbicide, simazine, occurred in 1958 and this also encouraged corn expansion, especially with other herbicides to follow.

Rugged farmland (and small town) north-east of Toulouse near where the flint variety, Lacaune originated

Major breakthroughs occurred soon after World War II. The first involved an obscure open-pollinated flint variety called Lacaune developed by farmers in the high-elevation (and comparatively cool) department of Tarn northeast of Toulouse. Successive generations were grown at high plant densities, resulting in a population of corn that was cold hardy, early maturing and tolerant to high plant densities.

Some seeds of Lacaune found their way to the INRA research program at Versailles (INRA stands for Institute National de la Recherche Scientifique), where a few generations of selection resulted in two inbreds, F2 and F7, that were released in 1946-47. The single cross, F2 x F7, was a flint hybrid with the same characteristics as Lacaune and good yield in its own right, but also of high heterotic vigour when crossed with early-maturing dent inbreds from the United States.

INRA released several flint-dent hybrids beginning in 1957, starting with INRA 200 and followed by INRA 258. Both were double-cross hybrids involving pairs Wisconsin inbreds and their single-cross, crossed with F2 x F7 (or F7 x F2, female parent listed first). INRA 200 and 258 were early enough in maturity to be grown as far north as Paris – permitting corn to mature for grain on these better French soils.

The Famous Hybrid, LG11, and Even Better Ones to Follow

This, in turn, led to the release of hybrid LG 11 in the late 1960s, by the cooperative Groupe Limagrain, based at Clermont-Ferrand. LG11 had the same Wisconsin-inbred/F7 x F2 parentage. LG 11 proven to be immensely popular and, along with the INRA hybrids, was responsible for a major expansion of corn production into the Loire River region of France, and northward, beginning in about 1970. Though I don’t have precise data, my understanding is that LG 11 may have represented 40% of French corn hectares during the mid 1970s.

I grew LG 11 myself and some other early-maturing French hybrids during the late 1970s in cooperative trials across Canada and France. We were interested in how the two groups compared in different environments. The flint-dent French hybrids generally had more cold tolerance in spring but were notably slower to dry-down in autumn. Some of these French hybrids were promoted for use on Canadian farms but the slow dry-down proved to be a major obstacle to farmer acceptance. The cold hardiness was attractive in Canada, but not so much as in Western Europe. (Canadian spring weather goes from cold to hot quite quickly, compared to the long, cool springs common across the Atlantic.)

The success of LG 11 in France prompted other French and American companies to consider related ventures and what followed were a number of joint ventures including France Maїs, a partnership with Pioneer based near Blois on the Loire River, and RAGT, a partnership with DeKalb, based at Rodez, north of Toulouse. One of the major developments was the hybrid Dea, a single-cross between a North American dent inbred and F2, released by France Maїs/Pioneer in 1981. Dea represented a large improvement in productivity (yield and stalk quality) and was widely popular, securing a major presence for Pioneer in France as well as continued expansion of corn production to the north.

One company that did not partner much with any North American partner was Groupe Limagrain. It continued to expand in France and then into North America. The former King Grain corn program based at Paincourt Ontario, marketer of Pride Seeds in Canada, is now part of AgReliant Genetics owned by Groupe Limagrain and Germany-based KWS.

(One of my most pleasant memories was that of serving as external examiner for a doctoral thesis defense of a Limagrain agronomist at the Université Clermont-Ferrand in about 1982. I don’t remember much about the thesis but I sure do remember the party to follow.)

My history stops here because I am not as familiar with the details of French corn development after I left the University of Guelph and joined the fledgling Ontario Corn Producers’ Association (OCPA) in 1983-1984.

It’s worth noting that my experience with AGPM was one of the reasons why I was so keen on the establishment of OCPA.

My impression is that French hybrids have become more dent like, and less flinty, with time – driven no doubt by a desire for faster dry-down in autumn and greater use of North American germplasm in corn breeding programs.

And French corn hectares have continued to grow, reaching 2 million ha in 1988 though with a gradual decline to about 1.5 million since then. The decline may be partly attributable to the inability of French farmers to grow transgenic hybrids with genes added for insect control and tolerance to glyphosate herbicide (very valuable in no-till agriculture).

I’ll close my brief history with an anecdote. When I visited France in 1975, I spent one late-August evening meal with an INRA corn breeder and his family in Montpellier. Before we left his research plot area for the day, he went to the very back of the research field and collected some ears of sweet corn – well hidden by taller corn nearby. At his home, he carefully closed the shutters before they boiled the ears for eating. It sure tasted good, but they didn’t want any neighbours to know we were eating corn.

Now you can buy sweet corn for eating anywhere in France. I saw several recent tweets from France promoting ‘popcorn’ (same word in French as English).

And I haven’t seen anything of late from the Catholic church condemning corn eating and corn farming.

Times change.

—

I express my deepest appreciation to Jean-Pierre Gay and his outstanding book Fabuleux Maïs, histoire et avenir d’une plante, which is the source of 99% of the information presented in this article. Thank you also to Mr. John (Jack) Watson of Des Moines Iowa, formerly of Pioneer International, who established the Pioneer/France Maïs corn breeding program near Blois and provided some information on the post LG 11 era. I thank l’Association Générale des Producteurs de Maїs for sponsoring Mr. Gay’s book and for its leadership in corn advancement.

Le Mont-Saint-Michel, Normandie, not a corn picture but one of my favourite views in France

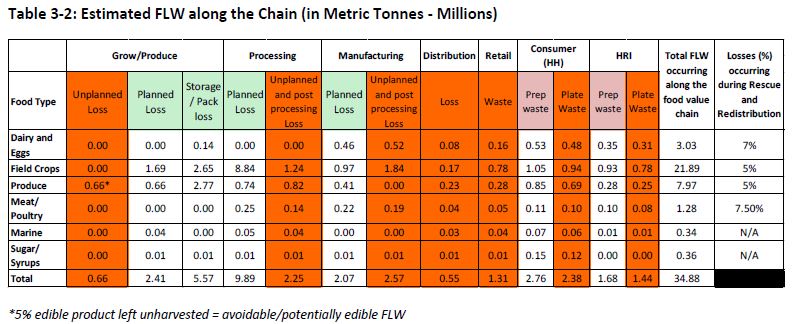

Food wastage has become a hot topic with everyone from the United Nations to numerous NGOs decrying the size of the loss and promoting opportunities to do better. Though I have been critical of some of these reports which usually don’t include any analysis of what a major reduction in food wastage would mean for the entire food system (smaller processing and retail industry sales and employment, as examples), I agree that less wastage would be beneficial in many ways.

Food wastage has become a hot topic with everyone from the United Nations to numerous NGOs decrying the size of the loss and promoting opportunities to do better. Though I have been critical of some of these reports which usually don’t include any analysis of what a major reduction in food wastage would mean for the entire food system (smaller processing and retail industry sales and employment, as examples), I agree that less wastage would be beneficial in many ways.